Queer + Christian // How A Christian-First Identity Causes Further Oppression

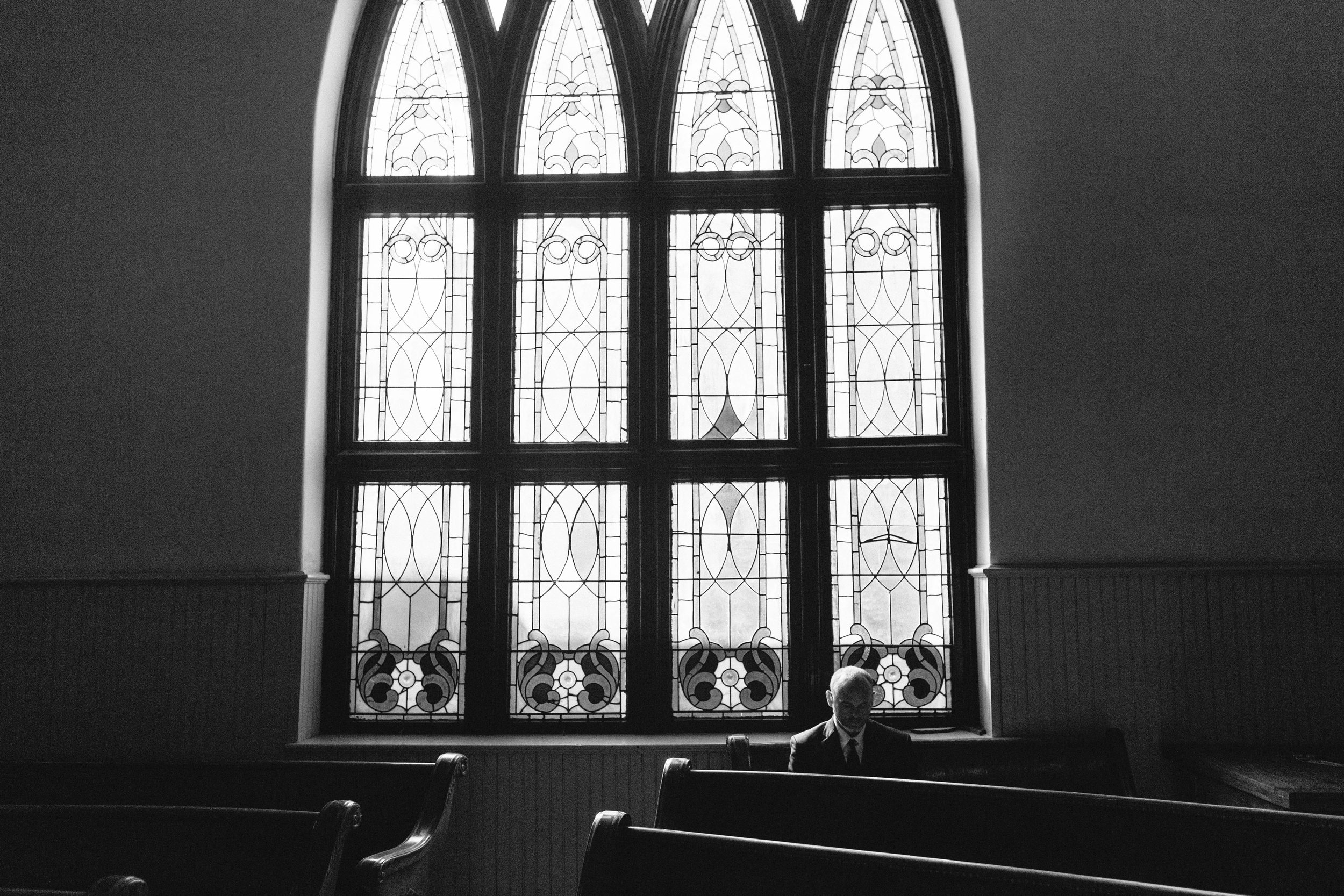

/Photo by Betty Clicker Photography

If there should be anywhere we can bring our most authentic selves, it should be in sanctuary spaces. Whether it's inside a physical building, outside in nature, or around the table in our homes, the times we gather to connect with the Creator and each other should be where we experience being known and radically loved. This being known is one of courageously sharing our lives with each other: where we don’t have to hide our pain, downplay our weird, or deny any part of who we are. This radical love is one of believing each other’s stories, honoring each other’s experiences, and standing alongside each other recognizing that our freedom is bound up in one another’s. These sacred spaces shouldn’t be where we are expected to be just one thing, but where the fullness of our identities are embraced. Sigh…help us, baby Jesus.

Being a queer, black woman who has often been in predominately white faith spaces, I have experienced a certain pressure to claim my Christian identity as my one, true identity. At the very least, the expectation is that I should be Christian first and that, “because of our faith, we don’t have to buy into the labels culture creates for us,” as stated by various pastors. But who is this way of thinking really benefiting? We know there are many things that make up who we are, and that the “labels,” whether the ones we give to ourselves, or the ones put on us by society are important, and they impact our experience in this world. Can we really live out our mission as Christians to love God and love our neighbors as ourselves if we close ourselves off to each other’s full identities?

A key component in my church experience has been an emphasis on authentic community. “Life change happens in small groups,” was a phrase I heard repeated often. Come to church on Sunday, but also outside of Sunday, “get plugged into a small group,” “do life together,” “know and be known.” When I was growing up, the community aspect was amazing! Parents willingly sent their kids off to participate in strange and fun things with the church youth group. The wildest thing I remember is a kid eating a live goldfish as a part of a challenge at an overnight lock-in at church. I have no idea why this was a thing, but we all cheered wildly! Our parents were hoping that through these antics, we’d develop a tight-knit Christian community and get to know God in the process. It worked for many of us, and during that time, as we were still figuring out who we were, it was comforting to embrace being a “new creation in Christ,” as my identity (from 2 Corinthians 5:17).

Intersectionality freed me to say that not only am I Christian, but I’m black, I’m a woman, I’m queer, and a whole bunch of other things, allllllllll at the same time.

As we aged, the authenticity and vulnerability in our community deepened as we supported each other through family struggles, financial hardships, new jobs, relationships, etc. We learned that developing a strong, personal relationship with God was key in getting through hard times and living life well. We gathered to study the bible and pray together, encouraging each other in times of pain to press into our relationship with God more. Various pastors and bible study leaders would remind us that we were all created in God’s image and advise that knowing God was the best way to then know ourselves—the character traits we were meant to display, the ways we were meant to live, etc. The issue is that even though we were in community, “knowing, and being known,” a very singular culture had been created, rooted in our efforts to identify fully/first as Christian. The culture left little space to bring the rest of ourselves into the picture, because the other things — race, cultural heritage, etc. — weren’t held with high value. With a singular focus on how our individual choices either connected us more to God or not, what was dangerously missing was any reflection on our intersecting identities and the systems of power and oppression that played a huge role in our experiences.

As I began to understand the workings of systemic oppression, I was able to view injustice in a more complex way, and I gained the ability to put language to my own experiences of being marginalized. In my attempts to widen the lens in certain faith spaces by bringing up race, gender, or another identifier in connection with our identities as Christian, there was pushback. When I discovered Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of Intersectionality, I felt the skies part and Jesus himself give me that knowing smile. It’s as if he was saying, “this is what you need, girl!” Intersectionality freed me to say that not only am I Christian, but I’m black, I’m a woman, I’m queer, and a whole bunch of other things, allllllllll at the same time. And that all of these things — the fullness of my identity — inform my understanding and experience in this world, the joys and the struggles.

When I enter church, I don’t get to take off my womanness or my blackness or my queerness and just enter as Christian. I enter as all of me, which includes the parts of my identity that our society privileges and the parts of my identity that our society oppresses. Shout out to Mother Lorde who preached to us all that, There is no thing as a single-issue struggle, because we do not live single-issue lives. I had an experience a couple of years ago at church where this truth could not have been clearer. The SCOTUS decision for marriage equality had just happened. During the worship time, my church took some time to acknowledge this historical moment. But, as the band began to play, I began to weep from sadness. I was thrilled by the way justice had been granted to my community with the SCOTUS decision. I was also overwhelmed with grief by the grave injustice of the Charleston massacre that had happened just over a week prior, also to my community. The intersections of my identity as a queer woman of color, who’d spent her early years in the pews of my grandmother’s AME church, had never been more palpable.

The times that we are in right now are real. People are hurting and dying and being locked away and shut out. If loving like Jesus loved is what we are supposed to do, then we must recognize the spiritual AND earthly systems at work holding people captive. Jesus modeled fierce, tangible love. That love stepped into messy places, it took routes of inconvenience, it pushed beyond the surface down to the root and then extracted it so that abundant life could grow. And yes, because of that radical love at work, the “dividing wall of hostility” the Apostle Paul talked about in the book of Ephesians came down, but people have been working to rebuild it ever since. God did not create us differently for our differences to be used to separate us into hierarchies, but that is what happened. We can’t now “Kumbaya” our way out, or “I don’t see color” our way out. The point is to see it. See it so we know how to pray, see it so we can tackle the dismantling process. And, see it so we can celebrate the goodness, the holiness of all of the things that make us who we are. In asking people to assimilate to just one thing, we miss out on the fullness of who they are and the fullness of who God is. In focusing on ourselves as Christian only or first, we deprive our communities of the authenticity we say we want. Let our faith spaces be ones where we can bring our most authentic selves and display transformative, radical love.

SHAE WASHINGTON

Shae Washington is obsessed with podcasts, coffee and her wife. She lives in the Washington, D.C. area, and she writes and speaks about social justice issues and her life as a gay Christian.